French Art Thief Who Pulled Off the Greatest Art Heist of All Time

From start to end, the biggest fine art heist in modern history lasted just 81 minutes. At 1:24 a.g. on March xviii, 1990, two men dressed equally police officers walked into Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. They overpowered two unsuspecting night security guards, and then duct-taped their victims to a piping and a workbench in the museum basement.

"Gentlemen, this is a robbery," the criminals announced.

The pair proceeded to remove thirteen treasured artworks on display in the lavishly decorated gallery, smashing the protective drinking glass of two Rembrandt paintings and cutting the canvases from their gilded frames. Just over an hour afterwards, the thieves fabricated off with a staggering collection of art that's valued today at $500 one thousand thousand.

Despite a flurry of press attention—and the $10 one thousand thousand reward offered by the museum for the items' safe return—the stolen works take never been recovered. Now, a new Netflix docuseries, "This Is a Robbery: The World's Biggest Art Heist," takes a deep dive into the thorny mysteries surrounding the criminal offence. As Adrian Horton reports for the Guardian, the four-function show builds on the reporting of the Boston World and WBUR, as well equally the FBI's ongoing investigation.

For amateur sleuths and art lovers alike, here are v key things to know about the infamous heist.

1. The thieves likely succeeded due to canny planning, luck and lax security.

Wealthy American art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner constructed her namesake museum out of her private, Venetian palazzo–inspired home in the promise that it would provide "for the education and enjoyment of the public forever." Only after her death in 1924, the museum vicious into financial busted. By 1990, the museum's security flaws were common knowledge among Boston's criminal aristocracy, making it a bit of a "sitting duck" for a heist, per the Guardian.

Late on the night of March xviii, the two thieves tricked the immature guards on duty, 23-year-old Rick Abath and 25-yr-old Randy Hestand, into buzzing them inside. Dressed in stolen police uniforms, the burglars pretended to be cops responding to a disturbance call linked to the rowdy Saint Patrick's Day celebrations taking identify exterior.

In one case inside, the criminals overpowered the hapless guards, disabled the security cameras and got to piece of work removing precious works of art from their frames. The thieves departed at ii:45 a.m. after making 2 carve up trips to their motorcar with the artwork in tow; the nighttime guards, their mouths duct-taped shut, remained trapped in the museum basement until the law, called in by the adjacent set of guards to get in at the museum, constitute them around 8:15 a.one thousand.

2. The perpetrators stole masterpieces by Vermeer and Rembrandt

but left the most expensive painting in the edifice untouched.

The thieves made a beeline for some of the museum'due south greatest treasures, including Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, the only known seascape painted by Rembrandt; A Lady and Admirer in Blackness, too by Rembrandt; and Johannes Vermeer'south The Concert, 1 of but dozens of the Dutch Old Master's paintings to survive today. They also picked up a self-portrait sketch by Rembrandt, five sketches by French Impressionist Edgar Degas, a small portrait of a man by Édouard Manet and an ancient Chinese bronze vessel.

Bizarrely, the burglars attempted to remove the flag of Napoleon's Imperial Guard from its frame just failed to do so, instead settling for a statuary, eagle-shaped finial, or ornament. Stranger still, the perpetrators left peradventure the about expensive work in the museum untouched: Titian's The Rape of Europa, which was hanging in a tertiary-floor gallery.

Per Robert M. Poole of Smithsonian magazine, the seemingly random assortment of stolen goods has confused authorities and journalists for decades.

"What continues to perplex those investigating the Gardner mystery is that no single motive or blueprint seems to emerge from the thousands of pages of testify gathered over the past xv years," wrote Poole in 2005. "Were the works taken for love, money, ransom, glory, barter or for some tangled combination of them all?"

Today, museumgoers can visit the Gardner in person or take a virtual bout showing what the thieves left backside: empty frames that hang eerily on the walls as a reminder of the loss.

iii. The FBI has named suspects in the crime, but the works remain missing.

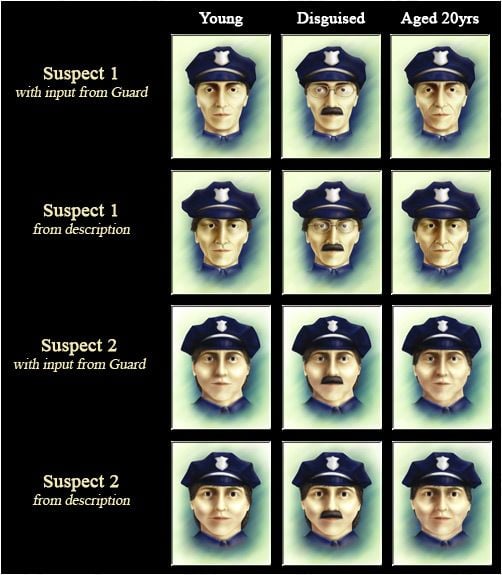

In 2013, the FBI announced that it had identified the 2 thieves with a "high degree of conviction." In 2015, the organization revealed the names of its primary suspects: George Reissfelder and Leonard DiMuzio, two associates of the late mobster Carmello Merlino. Both resembled law sketches of the criminals and died within one year of the heist.

The investigators as well said that they suspected the art was transported via organized criminal offence networks to Connecticut and the Philadelphia region, where the thieves attempted to sell the works on the black market. After those attempted sales, however, the artworks' trail goes cold.

Authorities were initially suspicious of the two young guards on duty that night. Abath, a self-described hippie and rock guitarist, was a regular on the dark shift. Because art crimes of this nature typically crave an within source, he was high on the list of possible conspirators.

Abath, for his part, has long denied whatever part in the heist, and government have generally cleared him as a person of involvement, reported Tom Mashberg for the New York Times in 2015.

"I was simply this hippie guy who wasn't hurting anything, wasn't on anybody's radar and the next day I was on everybody's radar for the largest art heist in history," he told NPR that same year.

In some other wrinkle, Abath'southward role in the drama once again came under scrutiny in 2015, when the Us Chaser's office in Massachusetts released a rare security camera video. The grainy footage shows Abath, who was on guard during the 24-hour interval of March 17, opening the same side doors used by the thieves and admitting an unidentified man in a waist-length coat and an upturned neckband, every bit the Times reported.

Overall, the museum'south security director, Anthony K. Amore, told the Times , the video "raises more questions than it answers."

4. Theories large and small abound, just certain answers are hard to come by.

Every bit the Guardian reports, dozens of theories ranging from conspiratorial to credible have cropped up over the years. About people, including the FBI, argue that the works traveled through organized crime networks in Boston: namely, the mob.

"This Is a Robbery" is less interested in "whodunnit" and more than interested in tracking where the paintings might have ended up. The narrative centers on Bobby Donati, a mobster who may accept organized the theft with beau criminal Robert (Bobby) Guarente in order to use the art every bit a bargaining chip to get their friend Vincent Ferrara out of jail, per Lauren Kranc of Esquire. Both Donati and Guarente are now dead.

Another former mobster, Robert Gentile, has long maintained his innocence despite a bevy of evidence pointing to his involvement in the law-breaking. The octogenarian was released from prison in 2019 after serving 54 months on an unrelated charge. He remains the only living person who likely has immediate knowledge of the 1990 heist.

The series briefly considers several wilder suggestions, including the theory that members of the Irish Republic Army (IRA) were involved in the criminal offence, notes Esquire. The directors also interviewed Myles Connor Jr., a colorful character and bedevilled fine art thief who was in jail at the time of the robbery. Connor provides essential context about how the underground art market operated during the 1990s.

"Researching the case was like learning the game of chess," docuseries director Colin Barnicle tells Boondocks & State's Norman Vanamee. "The more you know about it, the more options you see."

5. If you lot have information about the robbery, the regime and the Gardner Museum want your help.

People with data nigh the stolen artworks should contact security chief Amore at [e-mail protected].

The museum is offer a $x 1000000 advantage to anyone who provides information leading directly to the prophylactic render of the stolen works. Individuals whose information leads to the restitution of some, but not all, of the works will receive a fractional reward. Anyone who helps return the Napoleonic eagle finial volition receive a separate $100,000 reward.

Even someone involved in the theft itself can come forward; per the Times, the statute of limitations on the criminal offense has expired.

The Earth and WBUR's investigative podcast "Final Seen" helped publicize the theft upon its debut in 2018. Barnicle says he hopes the new series volition bring the plight of the paintings to an even wider audience—with the lingering hope that someone watching might know something new about the art's whereabouts.

"I call back if the docuseries doesn't assistance, and so they're gone," Barnicle tells Boston.com's Kevin Slane. "This [show] is like the biggest wanted poster in the world."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/five-things-know-about-isabella-stewart-gardner-art-heist-180977448/